GALLERY I

From Ashes to Empire

The Great Fire & Pittsburgh's Indomitable Spirit | April 10, 1845

On April 10, 1845, Pittsburgh burned. One-third of the city—1,200 buildings—consumed by fire. Lesser cities would have crumbled. Pittsburgh rebuilt in brick and stone, tripling its population in twenty years and emerging stronger than before. This is where Pittsburgh's character was forged: not in prosperity, but in the refusal to stay down.

The Morning After

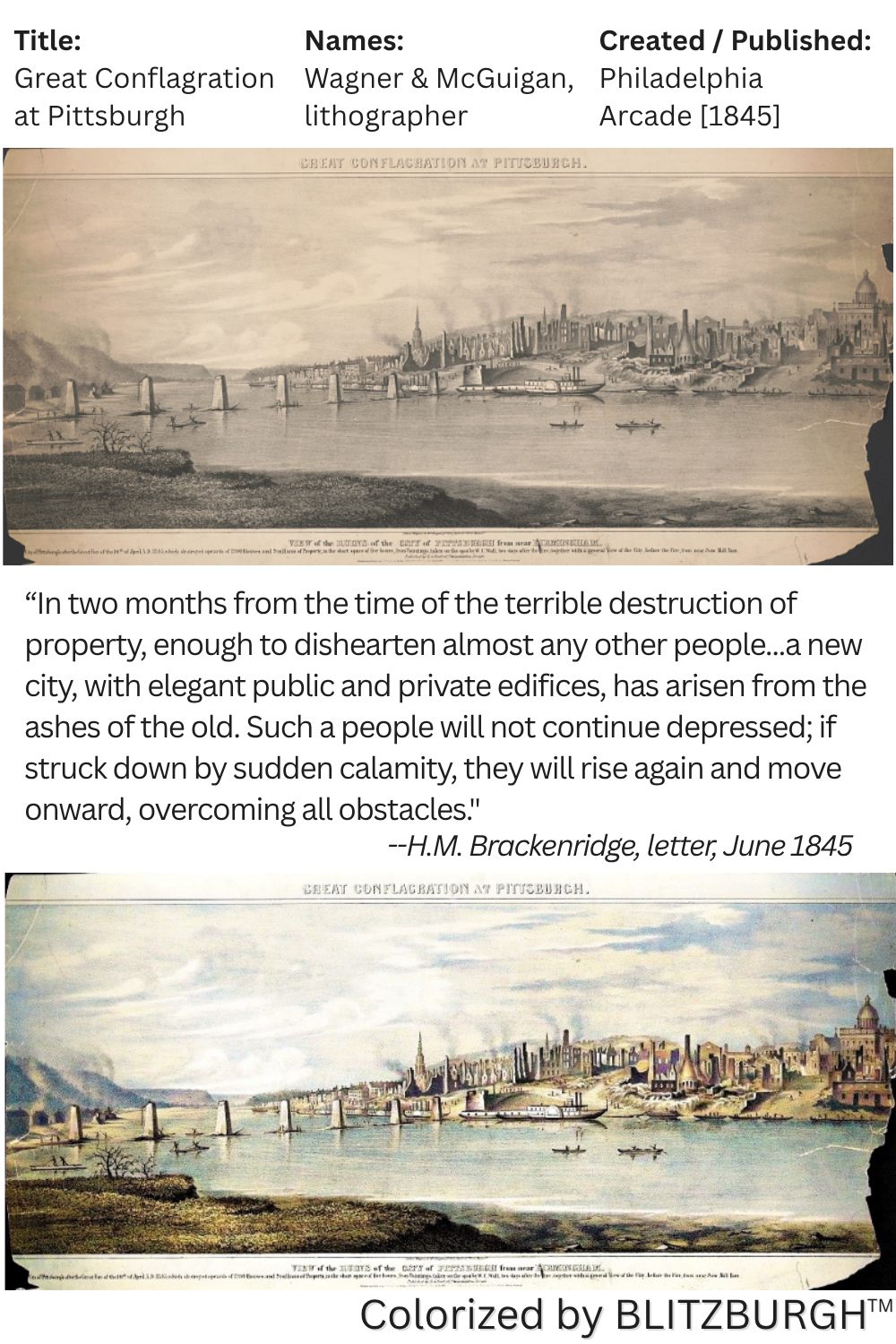

Wagner & McGuigan's lithograph captured Pittsburgh's destruction in 1845. One thousand two hundred buildings gone. Families homeless. Businesses destroyed. The city stood at the edge of ruin.

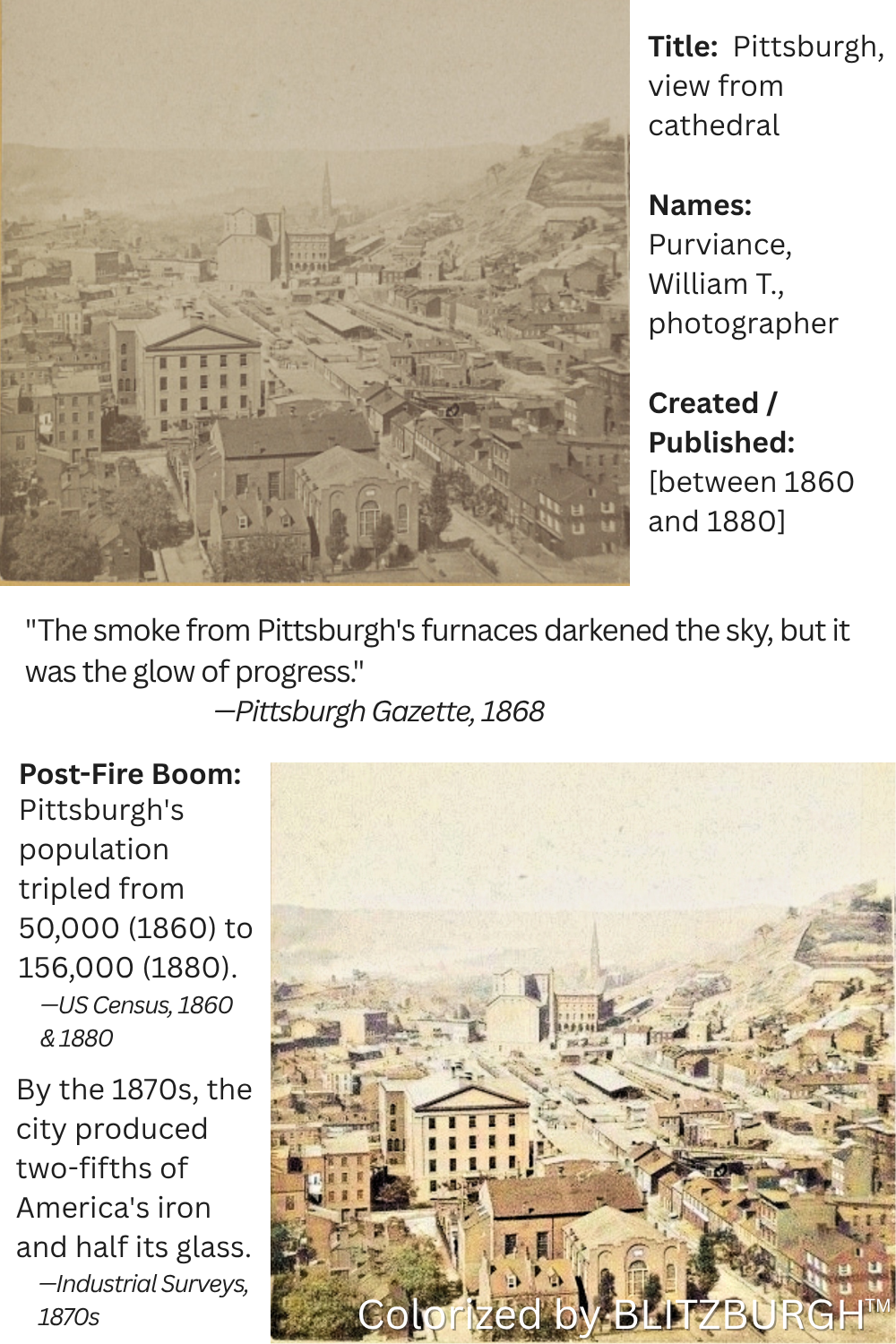

Rising from Ruins

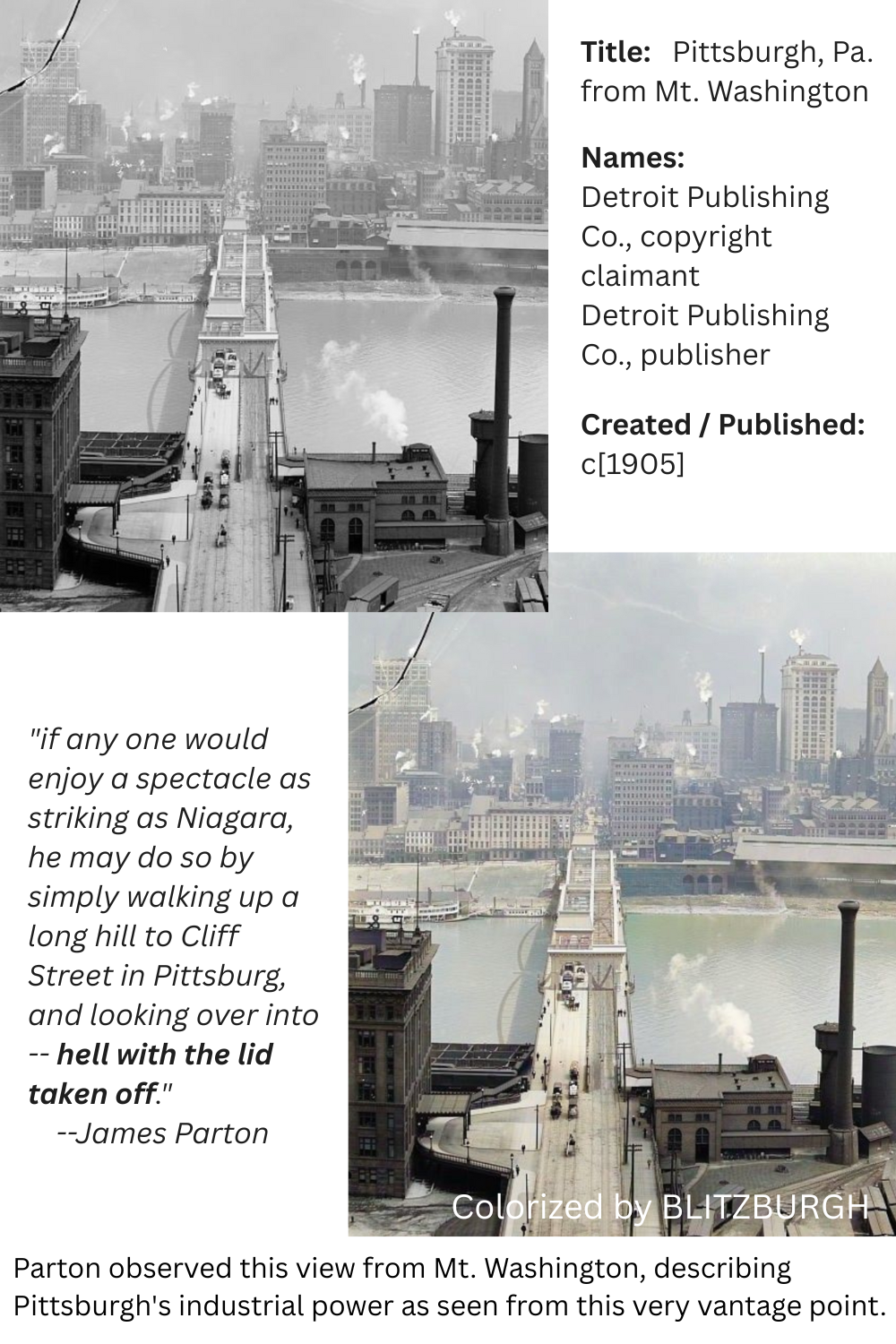

By the 1870s, Pittsburgh had transformed into an industrial powerhouse. Population tripled from 50,000 to 156,000. The city that refused to die became the city that built America.

"In two months from the time of the terrible destruction of property, enough to dishearten almost any other people...a new city, with elegant public and private edifices, has arisen from the ashes of the old. Such a people will not continue depressed; if struck down by sudden calamity, they will rise again and move onward, overcoming all obstacles."

—H.M. Brackenridge, letter, June 1845